The Tiara of Saitaferne: Priceless Treasure or Modern Error?

In April 1896 the illustrious Louvre Museum in Paris made an announcement that shook the world of archaeology. The museum had purchased a tiara from two Russian art dealers with the potential to rewrite ancient history.

In April 1896 the illustrious Louvre Museum in Paris made an announcement that shook the world of archaeology. The museum had purchased a tiara from two Russian art dealers with the potential to rewrite ancient history.

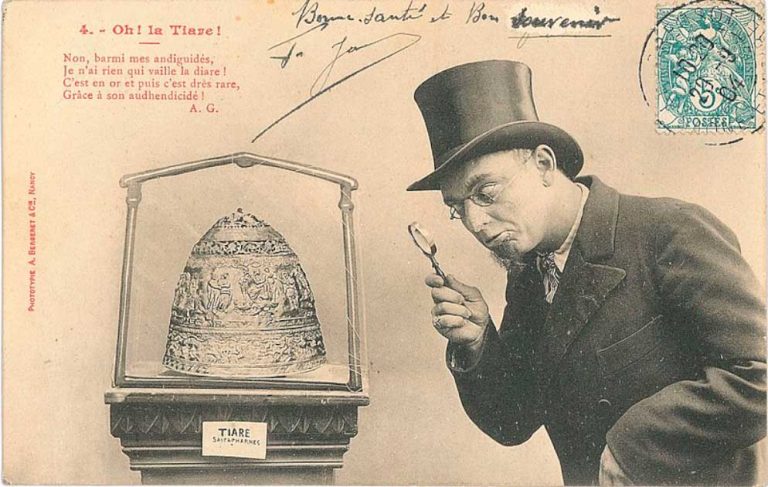

The tiara itself was around 7 inches (18 cm) tall with a domed helmet-like structure, weighing just over a pound (450 g) and entirely made of solid gold. Believed to be a gift to King Saitapharnes from the Greek colony of Olbia on the Black Sea coast, the tiara was ancient, predating Christ.

There were three significant parts of tiara, which was covered in exquisite relief depictions. Each part of the tiara had its own story, but there was no doubting the breathtaking quality of the original. Surely this was from the treasure house of the great king Saitapharnes himself.

Or maybe not.

A Beautiful Thing

The top of the Tiara of Saitaferne is worked in the Greek openwork ornamental style from more than two thousand years ago, featuring a crown with a snake having its head twisted in the form of a spiral. In the middle sector, the tiara featured some of the famous scenes from Homer’s Iliad, such as Agamemnon and Achilles quarreling with each other for Briseis.

The lower section of the artifact is significantly narrower in comparison to the middle one. It featured depictions of scenes from the everyday lives of Scythians, such as children learning archery, flora and fauna of the region, hunting scenes and horses being sacrificed. Furthermore, the Tiara also features an inscription which describes the story behind its origins.

In return for peace, the king had demanded a massive ransom from the inhabitants of Olbia. The inscription states that the people of Olbia complied with the king’s demands and created the Tiara as a gift.

- Michelangelo’s Fakes: Was the Artist A Fraud Before He Was A Master?

- The Dacian Bronze Matrix: 2,000-Year-Old Artistry

All the highlights in the tiara made everyone at the Louvre Museum in Paris and the general public believe that it was an original artifact from 3rd century BC.

Unanswered Questions

The doubts about the authenticity of the Tiara of Saitaferne gained momentum as the Louvre proudly showcased the artifact. As details about the transaction emerged, it appeared that the Louvre had not been lucky enough to find an ancient Scythian tiara, but had instead been the victims of a scam.

The two Russian art dealers who had sold the tiara, Schapschelle Hochmann and his brother Leiba Hochmann had forged the tiara with the help of a skilled goldsmith Israel Rouchomovsky. Apparently, they had asked the goldsmith to create the dome-shaped crown out of solid gold.

The Hochmann brothers made Rouchomovsky believe that the artifact was for a friend. Interestingly, the brothers also offered books on Greek mythology and drawings as well as details of recent excavations to help Rouchomovsky create a historically accurate artifact.

Rouchomovsky completed the artifact and handed it over to the Hochmann brothers in 1894 without a second thought. He believed that the crown was a gift for an archaeologist friend of the brothers and collected his commission for the work.

Several months passed. Then, the brothers put up some of what they called “recently discovered” Russian antiques on display in Vienna in 1896. Just over a year before the Hochmann brothers put up their display a Vienna newspaper had published an interesting news in 1895, which may have prompted their plan.

The news piece suggested that Crimean peasants had made some remarkable discoveries of Russian antiquities and had fled Russia out of the fear of confiscation of their finds. The Hochmann brothers may have realized that these stories could be used as a shaky provenance for artifacts such as the tiara.

Towards the end of the 19th century, European museums were actively seeking Greek and Scythian antiquities from Russia. Prior to the Tiara of Saitaferne, many noticeable finds at different sites such as the Seven Brothers, Kul Oba and Chertomlyk had strengthened the demand for Russian antiquities.

The blind race for antiquities is believed to be the reason behind the Louvre purchasing a forged artifact. But how did the Louvre not notice the fake? Did greed overcome prudence?

Truly a Fake?

The Tiara of Saitaferne in possession of the Louvre Museum in Paris is, sadly, a fake. How did the Hochmann brothers manage to fool one of the biggest museums in the world?

- Beringer’s Lying Stones: How did a Professor find Fossils of God?

- What is a Roman Dodecahedron?

Before the Louvre, the British Museum as well as the Imperial Court Museum in Vienna had passed on buying the tiara, clearly something was amiss with the forgery. However, Louvre acted more recklessly and saw it as an opportunity to grab a historical artifact before others could realize its value.

Apparently, the Louvre paid almost 200,000 francs for the tiara. All that money, and within a few days of putting it on display, many questions started floating around about its authenticity.

Some of the notable critics such as Adolf Furtwangler and Professor Vesselovsky of St. Petersburg pointed out the issues in the tiara. However, the Louvre disregarded the criticisms as outcomes of spite.

Subsequently, the war of words between the Louvre and the Parisian press started, which would last for around 6 years. The Tiara of Saitaferne drew criticism primarily for the state of preservation, which showcased damage in the non-essential areas only.

Finally, the mystery about the fake artifact came to light as a friend of Rouchomovsky, Lifschitz, published a letter to a newspaper in 1903. Rouchomovsky was brought to Paris for attesting to the claims made by Lifschitz in the letter.

Lifschitz had seen the tiara while Rouchomovsky was making it and did not hesitate in pointing out the scam. Rouchomovsky offered the details about the Greco-Scythian artifacts he had based his work on as well as the books he referred for creating the three parts of the tiara. The Louvre also asked him to prove his skills and offered him a sheet of solid gold.

Almost halfway through his work, the museum realized that this artist had the skills to build them another tiara. They saw that they had committed one of the biggest blunders by missing the important warning signs. Hey, at least they admitted it.